Percieving Colors

Teaching people to understand colors as a sound in Virtual Reality.

Overview

My second non-machine learning project, again expanding on a class project. Utilizing virtual reality (VR), I explored teaching people how to percieve colors as a sound, using colors that correspond to the visible color spectrum.

Abstract

Virtual reality (VR) is a developing technology with the potential to enhance perceptual abilities in users. Individuals with visual deficiencies (such as color blindness, low vision, and others) do not perceive colors accurately in a VR environment. In this paper, we present an innovative technique that converts sound to color perception within a VR framework. This method maps seven fundamental colors from the visible color spectrum, to specific piano notes on the major scale, allowing color perception through sound. Implementation involves four phases: initial training, three specific tasks (organization, selection, and Stroop test), a VR chromesthesia experience, and a qualitative post-study survey. The results of the user study demonstrate encouraging kappa values of 0.73, and 0.52, for the selection task and Stroop test, respectively, reflecting successful learning and comprehension of the associations between colors and sounds. Importantly, the therapeutic chromesthesia experience in VR created an immersive and pleasant user experience in VR. This investigation paves new paths for using sound-based color perception to improve accessibility and therapeutic applications in VR environments.

Training

To initiate training, participants were placed in a long hallway adorned with the visible light spectrum on both the floor and the walls. As they walked down the hallway, they encountered tones corresponding to each color segment, beginning with red and ending with purple. Each tone persisted as long as the participant remained on the associated color, allowing for extended immersion if desired. This setup facilitated a visual and auditory understanding of the color spectrum, enabling participants to learn the correlation between specific colors and their respective tones, particularly for similar-sounding colors such as green and cyan. Participants were allowed to revisit the hallway multiple times to become familiar with the tones and colors.

At the end of the hallway, participants entered a room containing 21 objects—7 colored ducks, 7 colorless ducks, and 7 colored basketballs. A top-down view of our VR training room is shown in. Participants were required to spend a minimum of 15 minutes there. Paricipants were instructed, provided on the wall, to interact with each colored duck at least once and to spend at least 10 seconds with closed eyes, mentally mapping the sound to the color. The colorless ducks functioned as auditory \textit{flashcards}, each emitting a tone linked to a specific color. Participants could use these to guess the color and then verify their guess by finding the corresponding colored duck, even though no feedback was provided. To maintain an engaging VR learning experience, the colorful basketballs were designed to be interactive, enabling attendees to practice shooting them into a bucket, thus enriching the sensory experience.

Task 1 (Ordering)

In the first task, participants were presented with sets of 3, 5, and 7 colorless ducks arranged on successive tables. Detailed instructions were provided at the initial table, which held three ducks, and participants were encouraged to ask any clarifying questions before beginning. Each table was timed to monitor task completion speed. Upon interaction, each duck emitted a tone that corresponded to a specific color. This task was multifaceted: it evaluated participants’ initial ability to associate tones with colors, acted as a selection filter for subsequent phases, and reinforced the color learning acquired during the training phase. The complexity of the task increased progressively—starting with three ducks representing the primary colors (red, blue, green), expanding to five with the addition of intermediate colors (orange and cyan), and culminating in seven (expanding to yellow and purple) to encompass the full visible light spectrum. This progression was designed to allow participants to reconstruct the visible light spectrum using auditory cues alone, thus deepening their understanding of color perception through sound.

Task 2 (Selection)

Task two marked the first evaluative task of the experiment, where the participants were presented with four tables, on each of which five colorless ducks were placed. Upon spawning, the participants found instructions at the first table that guided them through the task. Each table displayed a randomly assigned color to each participant. Participants were required to select the duck that emits a tone corresponding to the color displayed and place it in a bucket in front of the table. With only five ducks available, participants had to rely on their knowledge of the color-tone associations rather than trial and error. Furthermore, participants could place only one duck in the bucket as their final decision. Additionally, the time taken to complete each table was recorded to investigate potential correlations between task completion speed and accuracy.

Task 3 (Stroop)

The second and final evaluative task of our experiment adapted the Stroop test to explore the interplay between visual and auditory perception of colors. In this variant, participants were presented with a single table displaying seven colorless ducks. Traditionally, a Stroop test challenges participants to name the color of the text, which contrasts with the word itself (e.g., the word ‘red’ printed in blue ink). In our auditory-visual version, participants began by selecting a duck from the left side of the table and moving rightward. Each selected duck visually changed color and simultaneously emitted a tone corresponding to a potentially different color. Participants were required to correctly identify the duck’s color based on auditory cue alone, without relying on visual cues or comparisons with other ducks, for the initial attempt. They were allowed one initial attempt per duck, with the option of a second attempt, if needed. We also recorded participants’ total duration on this task to assess both their reaction times and accuracy under conditions of conflicting visual and auditory stimuli.

Results

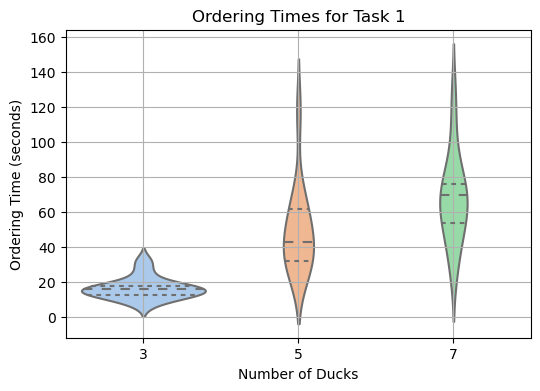

Violin plot illustrating the time participants spent at each table during the ordering task. Although participants completed the tasks quickly, many chose to spend additional time at the tables to reinforce their understanding of the visual light spectrum through auditory cues alone. This additional time indicates a deeper engagement with the learning objectives, as participants sought to ensure accurate representation of the color spectrum without visual assistance.

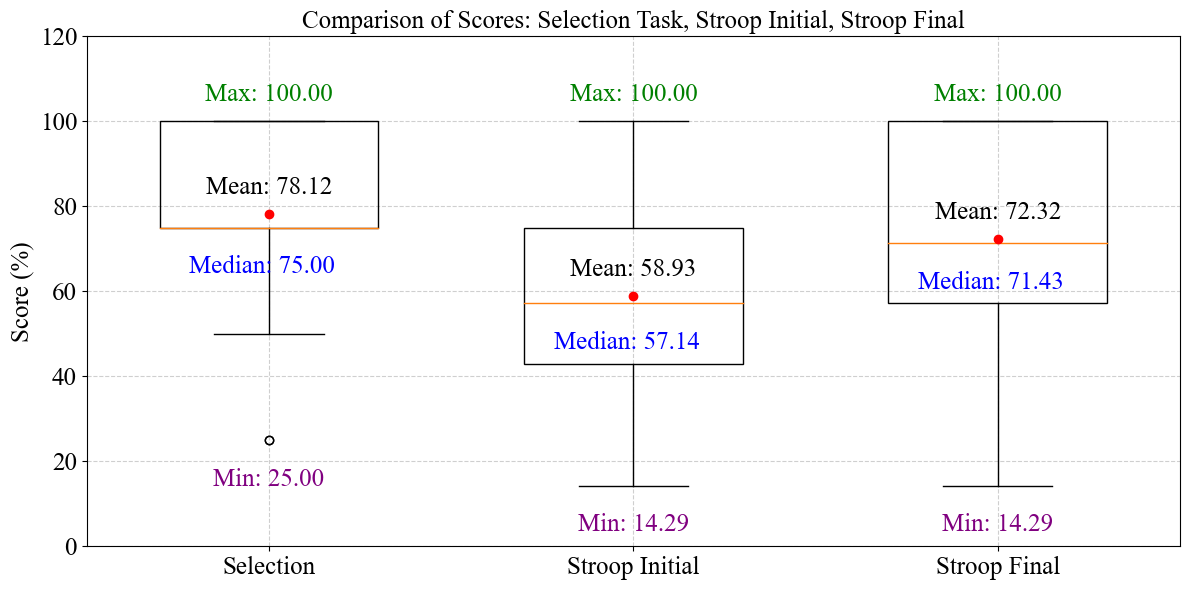

Box plots display outcomes from the selection task (Task 2) and Stroop Test (Task 3), where participants were allowed one initial guess per duck, and a subsequent second guess. These plots show variation in accuracy for Task 2, with an average achievement of 78.12\%, and some participants only identifying one correct duck out of four. This indicates diverse levels of proficiency in linking auditory signals with colors. In Task 3, the challenge was heightened by the presence of conflicting visual and auditory stimuli. Nevertheless, the data shows a praiseworthy capacity to integrate these conflicting cues, with an overall trend towards moderate success. The results underscore the ability of participants to adjust their perceptual approaches in response to intricate sensory settings.